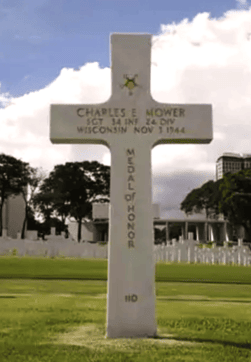

Remembering the "Gallant Initiative" of Sergeant Charles Edmund Mower

Two and a half years after his reluctant departure from the Philippines, US General Douglas MacArthur fulfilled his defiant pledge:

“I shall return.”

While the celebrated General enjoyed a hero’s welcome, on the liberated sands of Leyte Island, Sergeant Charles Edmund Mower pushed inland, battling Japanese forces for Leyte’s complete and final liberation…

Joining the US Army fresh out of high school, in February 1943, Charles would’ve joined earlier, were it not for the eagle-eyed recruiter who saw through his age…

Eventually assigned to the 24th Infantry Division, the “baby-faced” Wisconsinite soon proved his “soldiers’ mettle”; first, during a series of intense combat exercises; and then, in the brutal campaign for Japanese-held Hollandia, Indonesia.

From there, Charles and the 24th set sail for the Philippines, where, within an hour of storming the Leyte beaches, they secured the beachhead for MacArthur’s iconic landing.

Pressing their advance through Japanese-infested jungles and mountains, Charles and his squad freed several key towns and villages, before being halted by a well-entrenched line of dogged defenses…

Pinned down by an unrelenting barrage of machine gun fire, deaths and casualties mounted, including, not just one of Charles’ closest friends – when he "took a round to the head” – but also, his squad leader, when he fell in a withering hail of lead.

Thus, realizing command suddenly fell upon his shoulders, the coolheaded 19-year-old swiftly rose to the occasion, rallying and telling his surviving compatriots:

“We’re gonna silence those Jap emplacements!”

Thence, launching a daring assault to eliminate them, Charles led his men into the raging stream that separated them from their objective when, mere seconds after entering, he was struck by a blistering burst of bullets…

Gravely wounded, yet still “compos mentis”, the unwavering Sergeant refused both medical aid and evacuation, insisting:

“For as long as I’m breathing, I’m leading this mission!”

Crawling to a solitary ridge, semi-submerged in the middle of the stream’s bed, it was there, on this day in 1944, Charles gathered what little strength he had left and, drawing hostile eyes away from his comrades, gave his life, so they could neutralize the Japanese threat.

A year and some months later, when the “intrepid infantryman” was awarded the Medal of Honor for his selfless sacrifice, his admiring commanding officer told his beloved parents:

“Had it not been for your son’s gallant initiative, the enemy would have decimated his entire unit.”

Thanks to Charles’ “magnificent leadership”, however, his brothers-in-arms not only “survived the hellacious engagement”; but, “like the grateful nation he served, will forever be indebted to his courage.”

Addendum 1: -

US General Douglas MacArthur (center) fulfilling his defiant pledge to return to the Philippines.

Recalled from retirement, in July 1941, to become Commander of United States Army Forces in the Far East, then 61-year-old MacArthur arrived in the Philippines six years earlier, in 1935.

Asked by Filipino President, Manuel Quezon, to build him an army, the latter MacArthur raised, equipped, and trained, before leading in battle when the Japanese invaded in December 1941.

Despite concerted efforts to slow the Japanese advance, MacArthur’s forces could not hold them, thus compelling him to relocate his headquarters from Manilla to the fortified island of Corregidor.

There, MacArthur announced his intention to “share the fate of the garrison”; only for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to overrule his intent, by ordering him to “make arrangements… to leave as quickly as possible.”

Thence evacuated, on March 11th, 1942, MacArthur and his family eventually arrived in Adelaide, Australia, where, on being congratulated for his "remarkable escape" from the Philippines, the pipe-smoking General famously proclaimed:

"I came through; I shall return."

Addendum 2: -

The American invasion armada setting sail from Seeadler Harbor, Papua New Guinea, for “Operation King II” – the US-led liberation of Leyte island.

Addendum 3: -

Charles’ comrades storming the bullet-swept beaches of Leyte Island.

Landing ashore on October 20th, 1944, the amphibious invasion of Leyte was crucial, not just for securing its liberation, but also, for severing Japan’s vital sources of rubber, oil, and other war-fuelling materials.

Spearheaded by four divisions of the US Sixth Army, the latter fought the early stages of its campaign concurrent with the largest naval engagement in history – the Battle of the Leyte Gulf – which, by the time of its bloody conclusion, on October 26th, 1944, culminated in the near-total destruction of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Two months later, on Christmas Day, 1944, American land forces eliminated the last line of Japanese defenses, and, shortly thereafter, General MacArthur proclaimed:

“Resistance has ended.”

Despite ending with the tragic loss of more than 15,000 Americans killed and wounded, the deaths of 65,000 Japanese not only made it impossible for them to maintain their stranglehold on the Philippines; but, it destroyed the “cream” of their remaining army.

Addendum 4: -

Japanese Kamikaze pilots, swarming US Navy warships and carriers during the Battle of the Leyte Gulf.

Launching wave after wave of Kamikazes, on October 25th, 1944, their deployment marked the first, mass organized use of suicide bombers in the Pacific.

Sinking several dozen US Navy vessels, and killing more than 7,000 Americans, the Japanese expended no fewer than 2,600 aircraft on their Leyte “Divine Wind” missions, at the cost of over 4,000 airmen.

Addendum 5: -

Japanese sailors aboard the stricken, flagship aircraft carrier, “Zuikaku”, raise their hands in one final salute as their national flag is lowered.

Of the more than 70 Japanese ships that sailed in defense of Leyte, 26 were sunk by American forces, including the “Zuikaku”; three light carriers; three battleships; six heavy cruisers; four light cruisers; and nine destroyers.

Resulting in the loss of over 12,000 of its best sea, air, and crewmen, the Imperial Japanese Navy would never recover from its crushing defeat during the Battle of the Leyte Gulf.

Addendum 6: -

A lone US Navy Curtiss SB2C “Helldiver” flying high above a burning Japanese tanker, set ablaze during the Battle of the Leyte Gulf.

All told US Naval aviators sank more than 80% of frigates that the Japanese sent to resupply and reinforce their besieged forces on Leyte Island.

Addendum 7: -

Charles’ comrades pinned down by the Japanese “welcome party” they received upon storming Leyte’s fiercely defended beaches.

Addendum 8: -

Charles' brothers-in-arms pushing inland from their hard-fought-for beachhead on Leyte Island.

Addendum 9: -

One of Charles’ compatriots taking cover with “General Doug”, the German Shepherd, on one of Leyte’s bomb-cratered beaches.

Addendum 10: -

An imposing battery of 203mm M115 howitzers from the US 456th Field Artillery Battalion, preparing to unleash a barrage of cover fire in support of Charles and his comrades.

Addendum 11: -

Charles’ comrades engaging Japanese troops in the ruins of one of Leyte’s bomb-ravaged villages.

Addendum 12: -

Charles’ comrades pursuing Japanese forces during a fighting withdrawal on Leyte Island.

Addendum 13: -

Charles’ comrades trudging waist-deep through one of the many swamps they navigated during their liberation of Leyte.

Addendum 14: -

Filipino volunteers ferrying supplies to Charles’ comrades of the 1st US Cavalry Division, fighting in the jungles of Leyte island.

Addendum 15: -

Three of many Japanese snipers spotted and “dropped” by Charles’ comrades in Leyte’s jungle-covered swamps.

Lying face down in the muddy water, the Japanese snipers proved a “lethal menace” to the advancing American soldiers, killing and maiming countless.

Addendum 16: -

US Navy Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) disembarking supplies and reinforcements on Leyte’s recently liberated beaches.

Addendum 17: -

Charles’ compatriots raising the Stars and Stripes, two minutes after making landfall on Leyte Island.

Addendum 18: -

On July 17th, 1946, the US Army acquired this Tryon-class evacuation ship from the US Navy.

Then known as the “USS Tryon”, the Army proudly renamed the ship – “Sgt. Charles E. Mower” – in honor of their unwavering Sergeant.

Addendum 19: -

The veteran’s memorial in Charles’ hometown of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where his name sits front and center.

Born there on November 29th, 1924, Charles enjoyed what his siblings later described as an “idyllic American childhood, fishing, camping... and praying” in their parish church.

Despite his initial attempt to enlist fresh out of high school, both Charles' age and color blindness prevented him from joining the United States Marine Corps; and so, rather than abandon his endeavor to join the military, persisted until he was accepted by the US Army.

Later shipped out to Australia, where he completed a series of intense combat exercises, it was from there, Charles was deployed first, in the brutal campaign to secure Japanese-held Hollandia, Indonesia, and then, in the fearsome struggle to liberate Leyte Island.

Addendum 20 -

A sweeping view of Manila’s American Cemetery and Memorial. The memorial terrace (in the distance) is home to the cemetery’s chapel, next to which, stand two large hemicycles.

There, 25 mosaic maps illustrating American military successes in the Pacific theatre can be admired, along with two rectangular, limestone piers, honoring the names of more than 36,000 servicemen who, to this day, remain missing and unaccounted for.